Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander in Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet had been awake since 2 a.m. on his flagship the IJN Nagato, anxiously waiting news on the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Suddenly, the now infamous code word was excitedly shouted down the voice pipe from the radio room. ”Tora Tora Tora!” meaning that surprise had been achieved and the attack was a success.

Earlier, that same radio room on the Nagato had transmitted coded message number 676, "Niitakayama nobore (Climb Mount Niitaka) 1208" to the Japanese Strike Force (Kido Butai), which was then around 1513 km/940 miles north of Midway and steaming towards Hawaii. Mount Niitaka, located in Taiwan, was the then-highest point in the Japanese Empire, and the message meant that hostilities would commence against the U.S.

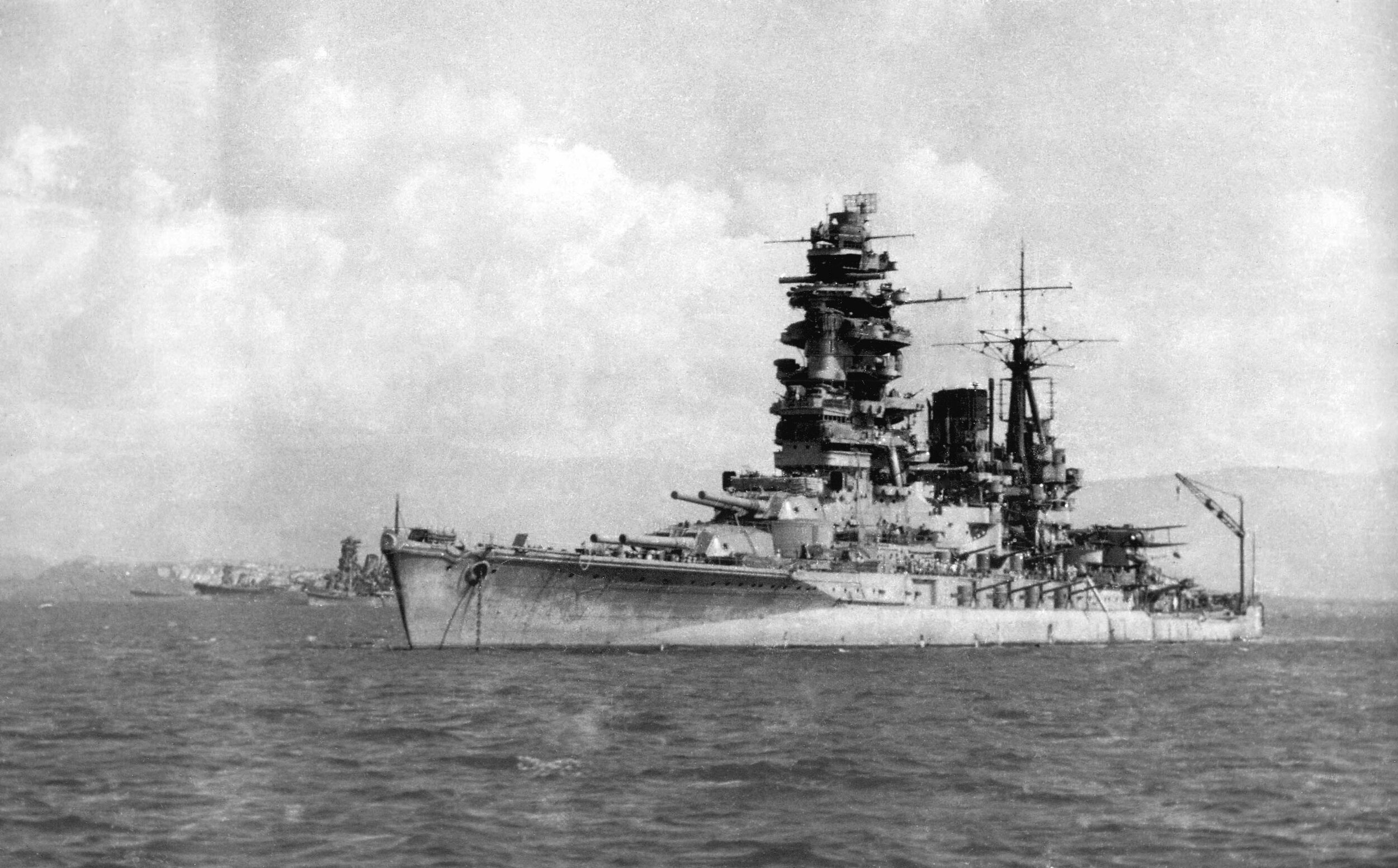

The Nagato was laid down at the Kure Naval Arsenal on August 28, 1917, launched just over two years later on November 9, 1919, and commissioned just over a year later on November 25, 1920. The ship incorporated a number of technological advances for the time, which were developed by the Japanese, and when she entered service she was the world’s largest and fastest battleship.

The Nagato was the first Capital ship in the world to be fitted with 16-inch guns. The eight guns were arranged in four twin-barreled turrets, two forward and two aft. The ship was extensively modified and refitted in the 1930s. The most striking modification was the fitting of a Pagoda mast. Pagoda masts were common on Japanese ships of the time; they had a number of platforms, lookouts, and shelters built upon each other and included watchpoints, searchlights, rangefinders, gun directors, and spotting points. The end result often resembled a pagoda temple, hence the name. Her displacement also increased at the same time to 39,130 tons and her length to 224 m/734 ft.

Surviving WWII

The Nagato was the only Japanese battleship to survive the Pacific War. Lack of fuel and materials to repair her meant she saw out the last months of the war as a floating anti-aircraft battery at the Yokosuka Naval Base. The Nagato was purposely taken over by US Navy personnel on August 30, 1945, before the official Japanese surrender was signed on board USS Missouri a few days later. The US Navy said this symbolized the unconditional and complete surrender of the Japanese Navy. After being selected for Operation Crossroads—the atomic tests at Bikini Atoll— preparations were made to get her ready for her final voyage. While no one at that time knew what the outcome of the atomic tests would be, it was always going to be a one-way journey for the once-mighty Nagato.

She was in a very bad state of repair, having been seriously damaged before the Japanese Surrender. Patched up, she left Japan on March 18, 1946, along with the Japanese cruiser Sakawa, which would also be one of Crossroads’ victims. With only two of her four propellers operational, the Nagato could barely manage ten knots. During the voyage, due to previous battle damage and a lack of maintenance, the Nagato started shipping water into her forward compartments. Her pumps couldn’t cope, and stern compartments had to be purposely flooded to maintain the ship’s stability. Ten days into the voyage the Sakawa broke down and the Nagato attempted to take her in tow, but then the Nagato lost one of her own boilers and, low on fuel, both ships ended up drifting helplessly in the mid-Pacific. To help, two Navy tugboats were dispatched from Eniwetok, and the Nagato was taken in tow by USS Clamp.

The Nagato continued to ship water, developing a seven-degree list, meaning she could be towed at only 1 knot. The Nagato finally arrived in Eniwetok on April 4th, where emergency repairs were carried out and the flooded compartments pumped dry. The repairs enabled Nagato to steam the last 322 km/200 miles to Bikini under her own power and on to her date with destiny. For the Able test of Operation Crossroads, the USS Nevada was the target ship and the Nagato was moored less than 400 m/1312 ft away on her starboard side, well within the expected fatal zone. The Able bomb, however, missed the Nevada, and the Nagato escaped relatively unscathed, suffering only minor damage. For the Baker test, the Nagato was once again placed well within the expected fatal zone.

The Nagato, however, rode out the tsunami of water that hit her following the explosion and although she was displaced almost 400 m/1312 ft from her original position, apart from a list to starboard again she appeared relatively unscathed. However, like the other survivors of the Baker blast, the Nagato was now seriously contaminated with radiation. Some minor attempts were made to wash the radiation off her decks, but she wasn't re-boarded and she gradually settled in the water over the next few days. As the sun set on Bikini on July 29th, the Nagato was still afloat. Her list was now ten degrees and her stern so low in the water that waves were washing over parts of the main deck, although she didn't appear to be in imminent danger of sinking. Whatever the future held for the Nagato, she wasn't leaving Bikini. She had survived the two atomic tests but was now seriously radioactive. Having seen the media fanfare as the USS Saratoga slipped under the waves a few days before, the Nagato decided she would go silently, without fuss, without attention. During the night her stern dipped deeper in the water, she rolled over and settled down on the seabed 52 m/171 ft below.

As the sun crept up behind Bikini Island the following morning, the Americans on Bikini gazed out at the empty spot in the lagoon which the Nagato had occupied the day before. She had gone.

As the sun crept up behind Bikini Island the following morning the Americans on Bikini gazed out at the empty spot in the lagoon which the Nagato had occupied the day before. She had gone.

Diving The Nagato

Diving the Nagato today, it soon becomes evident that everything about this vessel is big, and even after multiple dives, divers can barely scratch the surface of what the Nagato has to offer. Most dives start on the stern as the main mooring on the wreck is attached to one of the four propeller shafts. The first thing that comes into view are the four massive propellers that once drove the Nagato to 25 knots or more. These are now facing towards the surface, and behind them sit two large rudders.

Being over 4 m/13 ft in diameter, these are certainly impressive, but most divers quickly bypass these, leaving them for exploration towards the end of the dive. Like most battleships, due to her heavy topside weight, she turned turtle before sinking to the seabed 52 m/171 ft below.

It appears the stern hit the seabed first, and the stern section of the ship has now broken away behind the rudders and lies collapsed down on the seabed.

The once-mighty 16-inch guns haven't fallen away from their mounts and are still in their turrets in the stowed fore and aft position. The bow guns still have their end caps in place on the muzzle, but the stern guns don't enable divers to peer down the inside of the barrel. Sitting as they do in 50 m/164 ft, just exploring the aft guns and propellers can take up almost an entire dive.

Heading towards the bow from the stern, you eventually come to the huge Pagoda mast. The end of the mast broke away as it hit the seabed and now lies out to the right-hand side of the vessel and divers can still see the various upper levels, which included spotting points, rangefinders, and gun directors. Look more closely you can see voice tubes and remains of the lift that ran up inside the mast.

Forward of the Pagoda mast, you come to the bow guns. Depending on your dive plan, you might not have much time to explore the bow area, as it’s a 200 m/656 ft swim back to the mooring line. One option is to be dropped on the mid-ships mooring by skiff or do a free descent on the bow—that said, most divers still choose to swim from the stern as there are lots to see on the way and lots of nooks and crannies to explore.

Another option is to take a scooter; needless to say, scootering around the Nagato is a fantastic way to experience the wreck. If decompression starts to build up, one can come onto the top of the upturned hull, which stretches for as far as the eye can see, becoming an artificial seabed.

Turtles are often seen on the Nagato as well, and will often swim alongside divers. Due to the lack of human interaction in Bikini, they are far less skittish than turtles found elsewhere. For those who desire it, there are options for penetration both at the stern and bow as well as in the mid-ship sections of the ship.

Care needs to be taken, however, if one does decide to enter the wreck, as there are many old and discarded lines—some of which lead into areas that have since collapsed. Any serious penetrations should be planned properly and with the appropriate temporary lines laid. For most divers, there is enough to see on the outside of the wreck and the Nagato is an often requested repeat dive in Bikini.

On the way back, observant divers will notice sharks and other sea life coming into the cleaning station halfway back to the mooring. In fact, the Nagato is a good place to see sharks in general. Normally, there are many grey reef and blacktip sharks, and occasionally silver tips—and don’t be surprised to be sharing your deco time with a tiger shark or two swimming around you.

About The Author

Without Martin, The Dirty Dozen Expeditions wouldn't exist. A few years back, Aron and Martin spent a full year diving together in Truk Lagoon. One evening, after a day of demanding dives, they sat, had a beer, and came up with their ideal CCR wreck dive itinerary.

The first-ever Dirty Dozen trip was the result of that beer and the rest is history. Martin has lived in Truk for eight years with his family and works as the skipper of our expedition vessel in Truk and Bikini.

Photography by Martin Cridge, Aron Arngrimsson and Jesper Kjøller